Proof Derivative Matrix Requires Continuous Partial Derivatives

Review limit definition

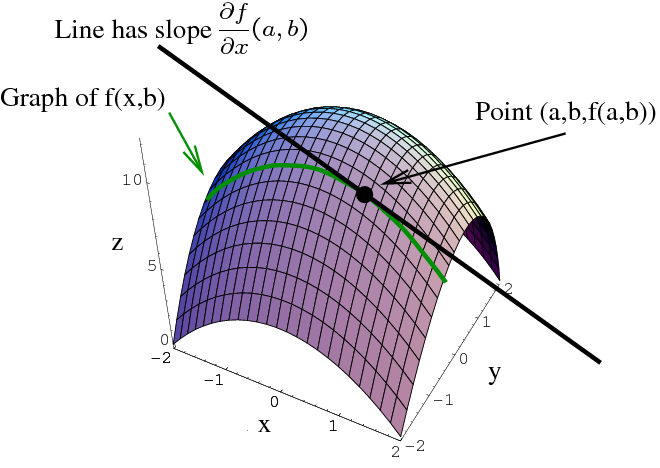

Recall that the partial derivative of $f(x,y)$ with respect to $x$ at the point $(a,b)$ is the same thing as the ordinary derivative of the function $g(x)=f(x,b)$: \begin{align*} \pdiff{f}{x}(a,b) = g'(a). \end{align*} (Here we think of $b$ as just a constant.) We illustrate this graphically as follows.

The green curve can be viewed as the function $g(x)$ and the black line is tangent to the green curve.

You may recall from one-variable calculus how the ordinary derivative was defined. It was with the nice formula \begin{align*} g'(a) = \diff{g}{x}(a) = \lim_{h\to 0} \frac{g(a+h)-g(a)}{h}. \label{eq:limitdef} \end{align*} You can use the the below applet to refresh your memory.

Ordinary derivative by limit definition. A function $g(x)$ is plotted with a thick green curve. The point $(a,g(a))$ (i.e., the point on the curve with $x=a$) is plotted as a large black point, which you can change with your mouse. The smaller red point shows the point on the curve with $x=a+h$, where you can change $h$ by dragging the blue point on the slider with your mouse. The blue line through the black and red points has slope given by \begin{align} \frac{g(a+h)-g(a)}{h}. \end{align} As you decrease $h$ toward zero, this slope of the blue line approaches the derivative $g'(a)$, as the above expression in this limit is exactly the limit definition of the derivative.

More information about applet.

To understand the formula for the slope of the blue line through the red and black points, note that the height of the red point is $g(a+h)$ and the height of the black point is $g(a)$. Therefore, the "rise" between those points is $g(a+h)-g(a)$. The "run" between the points is $h$. Rise over run is gives the slope of the line \begin{align*} \frac{g(a+h)-g(a)}{h} \end{align*} As $h$ approaches zero, this expression approaches the above definition of the derivative $g'(a)$. Hence, the slope of the blue line approaches the derivative $g'(a)$.

Since \begin{align*} \pdiff{f}{x}(a,b) = g'(a) \end{align*} we can apply the limit defintion of $g'(a)$ to conclude that \begin{align*} \pdiff{f}{x}(a,b) = \lim_{h\rightarrow 0} \frac{f(a+h,b) - f(a,b)}{h}. \label{eq:limitdefx} \end{align*} In a similar manner, we define \begin{align*} \pdiff{f}{y}(a,b) = \lim_{h\rightarrow 0} \frac{f(a,b+h) - f(a,b)}{h}. \label{eq:limitdefy} \end{align*}

Example with limit definition

Define $f(x,y)$ by \begin{align*} f(x,y) = \begin{cases} \displaystyle \frac{x^3 +x^4-y^3}{x^2+y^2} & \text{if } (x,y) \ne (0,0)\\ 0 & \text{if } (x,y) = (0,0) \end{cases} \end{align*} If we want to calculate the partial derivative of $f(x,y)$ at any point away from the origin $(0,0)$, we can use the usual formulas. However, if we want to calculate $\displaystyle \pdiff{f}{x}(0,0)$, we have to use the definition of the partial derivative. (There are no formulas that apply at points around which a function definition is broken up in this way.)

So, we plug in the above limit definition for $\pdiff{f}{x}$. We use the fact that $f(0,0)=0$ and \begin{align*} f(h,0) = \frac{h^3+h^4-0^3}{h^2+0^2} = \frac{h^3+h^4}{h^2} = h+h^2. \end{align*} Then, \begin{align*} \pdiff{f}{x}(0,0) &= \lim_{h \rightarrow 0} \frac{f(0+h,0)-f(0,0)}{h}\\ &= \lim_{h \rightarrow 0} \frac{f(h,0)-f(0,0)}{h}\\ &= \lim_{h \rightarrow 0} \frac{\displaystyle h+h^2-0}{h}\\ &= \lim_{h \rightarrow 0} 1+h\\ &=1. \end{align*}

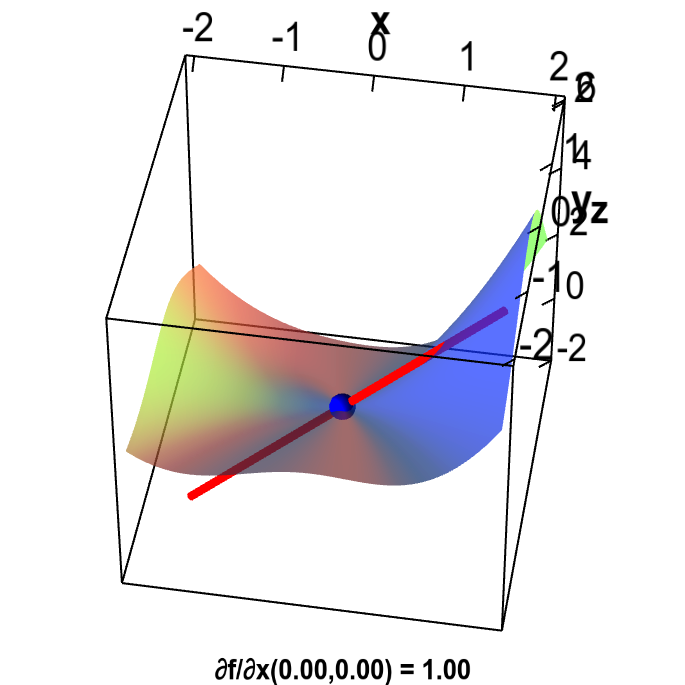

This partial derivative is illustrated by a tangent line of slope 1 in the below applet.

Applet loading

Example partial derivative by limit definintion. The partial derivative of a function $f(x,y)$ at the origin is illustrated by the red line that is tangent to the graph of $f$ in the $x$ direction. The partial derivative $\pdiff{f}{x}(0,0)$ is the slope of the red line. The partial derivative at $(0,0)$ must be computed using the limit definition because $f$ is defined in a piecewise fashion around the origin: $f(x,y)= (x^3 +x^4-y^3)/(x^2+y^2)$ except that $f(0,0)=0$. You can change the point $(x,y)$ at which $\pdiff{f}{x}(x,y)$ is evaluated by dragging the blue point. Since $\pdiff{f}{x}(x,y)$ is discontinuous around $(0,0)$, the derivative jumps as soon as you move the point.

More information about applet.

Source: https://mathinsight.org/partial_derivative_limit_definition

0 Response to "Proof Derivative Matrix Requires Continuous Partial Derivatives"

Postar um comentário